ONÈ!

“Onè” is a Haitian Creole greeting meaning “honor.” By saying “Onè!” I honor you as my interlocutor, and I honor your family, your ancestors and your community. In Haiti, the response to my “Onè!” would be: “Respè!”—indicating mutual respect.

Haiti deserves honor and respect for its unique history of freedom struggle—a gift to the world. But the country where I was born and raised, and Haitians in the United States, are often in the news for all the wrong reasons. Today, it’s Donald Trump and J.D. Vance’s canard about Haitians in Springfield, Ohio.

In 1804, Haitians, once enslaved by French colonizers, proclaimed “Tout moun se moun,” every person is a person—an affirmation of universal humanity that predates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and modern human-rights movements, including #BlackLivesMatter.

It was a time when white supremacists, beginning with the French Code Noir (Black Code) of 1685, had declared Blacks in Europe’s colonies in the Americas to be chattel. Today, white supremacist enablers lie about Haitians immigrants in Ohio.

Language has always been a loaded weapon in the history of oppression of those Frantz Fanon calls “the wretched of the earth.”

Take my native Haiti. There French is used by a small elite to enforce educational apartheid, marginalizing those who speak Kreyòl only.

Born into a French- and Kreyòl-speaking family, I was punished at school for speaking Kreyòl, considered “broken French” by parents, teachers, and most people in authority. Back then, I had no idea what linguistics was and what the definition of “language” was, and I did not realize the colonial violence at play.

After migrating to the U.S. in 1982, I began to understand language as a tool for oppression, thanks to works like Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature.

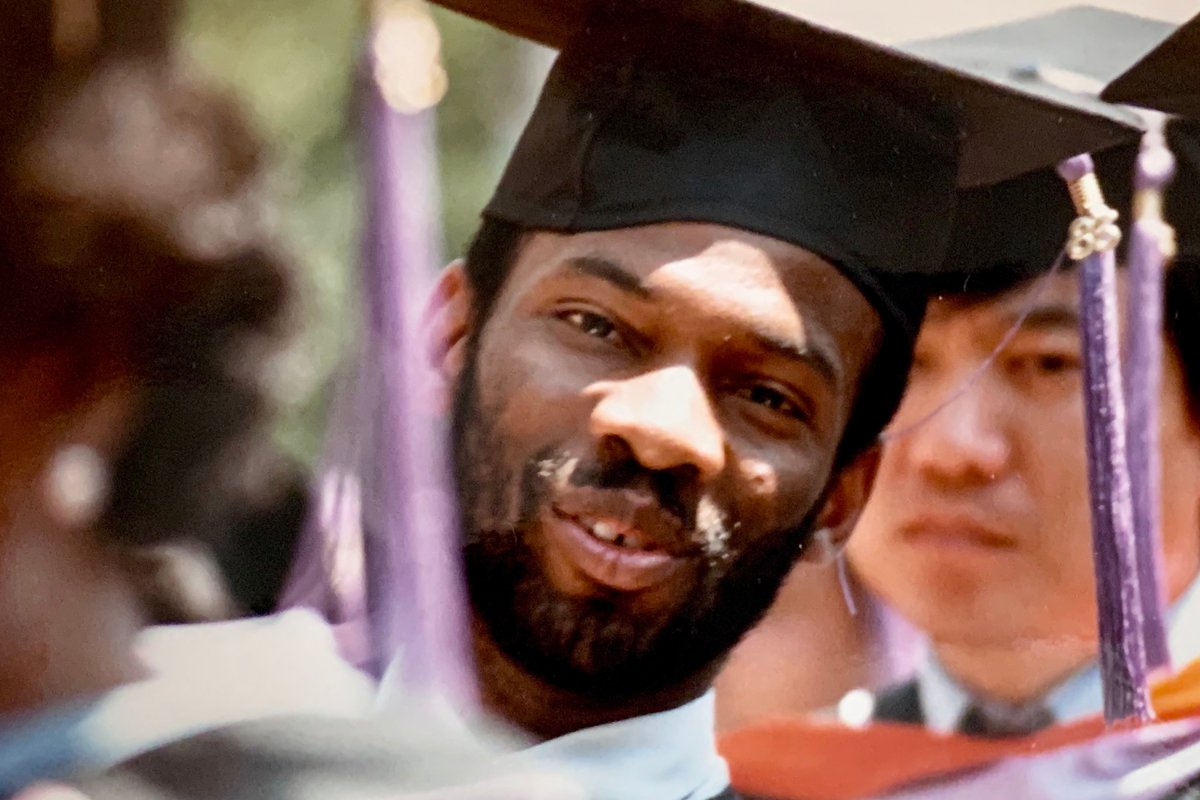

Michel DeGraff

For more than 30 years now, my research in linguistics has been a tool for what Bob Marley called “emancipation from mental slavery,” countering the widely held belief that Creole languages are somehow inferior and unsuitable for education.

In 2010, with MIT colleagues, I co-founded the MIT-Haiti Initiative, a silver lining around the dark cloud of the devastation of the January 2010 earthquake. Our mission is to leverage Kreyòl, technology and active-learning pedagogy to democratize access to quality education in Haiti.

Evidence shows that Kreyòl is far from inferior. As the mother tongue of all Haitians in Haiti, it enhances students’ learning outcomes across subjects like reading and writing, math, and science.

When students are liberated to learn in their mother tongue, they build new knowledge more effectively, including in second languages. Just as Kreyòl fueled the Haitian revolution of the late 18th century, it can drive our collective emancipation in the 21st century. The path to a liberated future in Haiti undeniably runs through the power of our sole national language—Kreyòl.

Contrast that with language employed as a tool to justify oppressive and repressive political agendas, fueled by lies that echo the 19th-century slanders by British historian James Anthony Froude.

Froude’s narrative dehumanized Haitians with his claims that we “eat babies” and “sacrifice children in the serpent’s honor after the manner of [our] forefathers.” Today, it’s accusations from Donald Trump and J.D. Vance that Haitians are stealing and eating dogs and cats. Froude’s discourse, just like that of Trump and Vance, mirrors medieval antisemitic blood libels about Jews sacrificing Christian children for Passover rituals. In Froude’s worldview, the only venues where “specimens of black humanity” can be found are among “servants in white men’s houses.”

By depicting Haitians as subhuman, Froude sought to justify slavery as beneficial. His disappointment in independent Haiti—where “no white man can own a yard of land”—led him to emphasize a racial hierarchy where only “philonegro enthusiasm” could elevate as hero Toussaint Louverture, one of Haiti’s most celebrated freedom fighters.

Today’s anti-Haitian rhetoric from Trump and Vance mirrors these very narratives of dehumanization. And they do not limit themselves to Haitians. They falsely accuse immigrants more generally of “poisoning the blood” of an America that they want to “make great again.” To me, it evokes Nazi language. The false narrative of immigrants poisoning America recalls the baseless HIV accusation in the 1980s when we Haitians were forbidden from donating blood.

Despite well-documented rebuttals, Trump keeps resurrecting claims like these to incite fear, xenophobia, and to gain votes by demonizing immigrants—Mexicans as rapists, criminals and drug dealers; Asians as coronavirus carriers; Haiti, El Salvador and Africa as “shithole countries;” Haitians as thieves who devour Americans’ beloved pets…

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Trump and Vance are not the only ones weaponizing language to “otherize” human beings. Project 2025’s Mark Krikorian, like Froude, bemoans that Haiti “wasn’t colonized long enough.” Benjamin Netanyahu and his cabinet weaponize words like “children of darkness,” “human animals,” “wild beasts” and “Amalek” by using them as descriptors for Palestinians, in the service of demonizing an entire people as such and erasing their humanity and history. This is akin to the mythical and much disputed narrative of Palestine as “a land without a people for a people without a land”—a myth that is still taught to some Jewish children.

This erasing of history is found among Trump’s political opponents as well. In the Trump-Harris debate, Kamala Harris overlooked more than one century of Middle Eastern history, implying that the Gaza conflict began in October 2023. Harris’ erasure of Israel’s history in Palestine, though framed in more polite language, mirrors Trump’s silencing of U.S. history in Haiti.

Hate speech transcends facts, aiming to exploit primal emotions about wedge issues for political gain, as analyzed in David Beaver and Jason Stanley’s book The Politics of Language.

Such harmful speech is a weapon of mass dehumanization.

As cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson have shown, the metaphors in such hate speech help form worldviews that otherize their targets as lesser humans to be disposed of through deportation, ethnic cleansing or worse.

These language-based tactics against non-or lesser Americans (as opposed to “real” Americans or “American Americans” à la MAGA) perpetuates a narrative of racial purity under threat, so voters must choose a savior to protect them from dark-skinned immigrants.

While concerns about immigration causing a strain on social services are valid, labeling Haitians in Springfield as “pests” is defamatory and has spurred dangerous threats, including bomb threats.

It matters not to Trump that Ohio officials, including the Republican Governor, have debunked these accusations about Haitians eating pets. They have highlighted that most Haitians in Springfield are law-abiding and legal residents who have helped revitalize the economy, and that the city’s migrants have lower crime rates than others. But still, Trump pushes the “migrant crime” myth to stoke fear and demonize immigrants.

Like in my work debunking dehumanizing myths about Creole languages, I believe that one way to resist attacks on our humanity begins with scholarship.

Katherine Taylor

Inspired by Noam Chomsky’s call to “the responsibility of intellectuals,” my MIT seminar this semester (Fall 2024) addresses “Language and Linguistics for Decolonization and Liberation in Haiti, Palestine and Israel.”

We examine how language, linguistics and education are enlisted, often underhandedly, for political gains, and wielded by colonizers and fascists to otherize and dehumanize—whether the “other” is a migrant, Jew, Arab, Palestinian, Chinese, Mexican or Haitian.

Conversely, we explore how language and linguistics can empower resistance.

Most of my MIT Linguistics colleagues have chosen a narrowly defined mission statement that excludes the socially responsible work that I and others, including those late colleagues who recruited me at MIT, have been committed to. This mission statement focuses on a particular vision of linguistics, which, although valuable, overlooks the importance of studying language in its social and political contexts.

Now, they’ve censored out of MIT Linguistics my seminar on language and linguistics in decolonization and liberation struggles in Haiti, Palestine and Israel. I have had to offer it for no credit, outside the bounds of my academic unit—which is how the seminar is unfolding, precisely because exploring the politics of language is crucial for comprehending how linguistic cognitive processes can propagate harmful ideologies.

Beaver and Stanley argue that such weaponization of language facilitates what Hannah Arendt famously called “the banality of evil,” the very thing that enables ordinary people to commit or witness atrocities in the course of apparently normal lives, as depicted in the movie Zone of Interest about the Nazis’ Auschwitz concentration camp.

It is no exaggeration to say that Trump and Vance’s rhetoric is the type of dehumanizing language that can lead to crimes against humanity as groups are viewed as lesser humans or worse (“vermin”!). History has shown this repeatedly—from Germany to Rwanda to the Dominican Republic near the border with Haiti.

And do not think that this sort of dehumanizing language is exclusively found among the alt-right. Indeed, there are self-declared “leftists,” even among my own colleagues at MIT, from whom I hear similar kinds of dehumanizing speech. For example, in May 2024, we heard one top administrator at MIT compare the alleged “danger” posed by students engaged in anti-genocide protests to the danger posed by… rapists!

As a Haitian, I myself have encountered harmful speech both from the broader community (I already mentioned the HIV story of the 1980s) and within academic circles, such as at MIT.

The argument to exclude my seminar from being an “official” MIT Linguistics class was based on skepticism from my colleagues about my expertise and scholarly competence in a field to which I have dedicated my entire career. It is now clear to me that some of their doubts may stem from a lack of familiarity with my work of the past 30 years and more or perhaps it is rooted in systemic biases—the sort that affects us all, often unconsciously.

After all, the same colleagues who claimed that I lack expertise and scholarly competence to organize a seminar about the weaponization of language also insist that no more than common sense is needed to analyze such weaponization.

Similarly, an inappropriate comment made by an MIT Linguistics colleague at a social gathering—a Thanksgiving dinner that I attended with my white girlfriend, now my wife—was painful: A racist joke about the allegedly larger-than-normal size of my private parts as an attraction to white women.

Was this a misguided attempt at humor rather than prejudiced malice? My hunch is that any group—even in higher education, even linguists—might end up so imprisoned in systems of oppression that they are unable to see the oppressive character of their own behavior toward the targets of their oppression.

Nevertheless, these examples show that the use of dehumanizing language is certainly not exclusive to extreme-right fascists. And we know we are in trouble when such language is found among the self-proclaimed “liberal left” of higher education.

Haitians, Mexicans, Chinese, Jews, Palestinians and other “wretched of the earth” have been prime targets of hate speech, but tomorrow it could be any group.

Dear Reader, your turn might be next. When language is weaponized to justify the oppression and destruction of populations as migrants or as indigenous in their homelands, no one is safe.

We do have the resources, such as Beaver and Stanley’s The Politics of Language, to counteract the weaponization of language for oppression and to promote emancipation, community-building and sovereignty. In a forthcoming book with MIT Press, I explore language and education for liberation in Haiti and similar communities that suffer from linguistic apartheid.

Other good news: Despite being censored away from MIT Linguistics, my seminar this Fall 2024 semester—on language and linguistics for decolonization and liberation in Haiti, Palestine and Israel—will be available on MIT OpenCourseWare.

This is my way to fight back, in scholarly fashion, against the use of language for dehumanization and oppression.

Linguistics for mental emancipation and self-determination and for peace and community-building is what I want to continue devoting my career to—now with case studies from Palestine, Israel and beyond—upholding the belief, like my African ancestors did, that every person is inherently and equally valuable.

Tout moun se moun…

Michel DeGraff is a professor of linguistics at M.I.T. His research interests include the theoretical and practical aspects of the use of language and linguistics in decolonization and liberation struggles, as in his native Haiti and in other post-colonies. He is currently working on a manuscript on the power of language, linguistics and education for self-emancipation and nation-building, to be published by MIT Press in 2025. With Prof. Haynes Miller at M.I.T., he directs the MIT-Haiti Initiative for the promotion of active-learning and Kreyòl in Haitian education; he is also a founding member of the Haitian Creole Academy, a fellow of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) and a former member of the Executive Committee of the LSA and a former representative of the LSA on the Science & Human Rights Coalition of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.