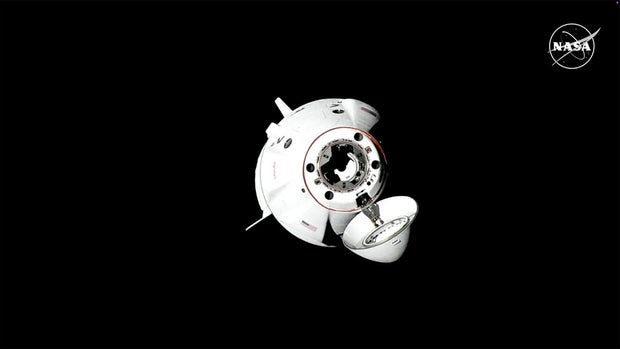

A day after launching from the Kennedy Space Center, a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft caught up with the International Space Station and moved in for docking Sunday, bringing a NASA astronaut and a Russian cosmonaut to the outpost to join two Starliner astronauts for a five-month tour of duty.

The rendezvous came amid word from SpaceX that it’s suspending Falcon 9 launches while engineers work to figure out what caused the crew’s Falcon 9 upper stage to misfire Saturday, after the Crew Dragon was released to fly on its own, resulting in an off-target re-entry over the Pacific Ocean.

Sen

SpaceX said in a post on the social media platform X that the second stage “experienced an off-nominal deorbit burn. As a result, the second stage safely landed in the ocean, but outside of the targeted area. We will resume launching after we better understand root cause.”

It was the second Falcon 9 upper stage anomaly in less than three months and the third failure counting a first stage landing mishap. It’s not yet known what impact, if any, the latest problem might have on downstream flights, including two high-priority October launches to send NASA and European Space Agency probes on voyages to Jupiter and an asteroid.

But the anomaly had no impact on the Crew Dragon’s 28-hour rendezvous with the space station, and the ferry ship, carrying commander Nick Hague and cosmonaut Alexander Gorbunov, docked at the lab’s forward port at 5:30 p.m. EDT as the two spacecraft sailed 265 miles above southern Africa.

Standing by to welcome Hague and Gorbunov aboard were Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and pilot Sunita Williams, now serving as commander of the space station, along with Soyuz MS-26/72S commander Aleksey Ovchinin, Ivan Vagner and NASA astronaut Don Pettit.

Hague, Gorbunov, Wilmore and Williams will replace Crew 8 commander Matthew Dominick, Mike Barratt, Jeanette Epps and cosmonaut Alexander Grebenkin when they return to Earth around Oct. 7 to wrap up a 217-day stay in space.

Wilmore and Williams took off on the Starliner’s first piloted test flight, a mission expected to last a little more than a week, on June 5. During rendezvous with the space station the day after launch, multiple helium leaks in the ship’s propulsion system were detected and five maneuvering jets failed to operate properly.

SpaceX/NASA

NASA and Boeing spent the next three months carrying out tests and analyses to determine if the Starliner could safely bring its crew back to Earth. In the end, NASA managers decided to keep Wilmore and Williams aboard the station and to bring the Starliner down without its crew.

They made that decision knowing the two astronauts could come home aboard the Crew Dragon launched Saturday. Two Crew 9 astronauts — Zena Cardman and Stephanie Wilson — were removed from the crew to provide seats for Wilmore and Williams when Hague and Gorbunov return to Earth in February.

When they finally get home, Wilmore and Williams will have logged 262 days in space compared to five months for Hague and Gorbunov.

The Crew 9 flight was SpaceX’s 95th launch so far this year. And it was the company’s third flight in less than three months to run into problems.

NASA

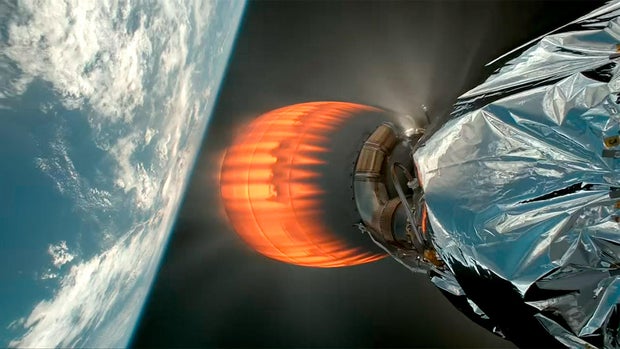

SpaceX recovers, refurbishes and relaunches Falcon 9 first stage boosters, which can land in California, Florida or aboard off-shore droneships. The second stages are not recovered.

Instead, SpaceX commands upper stage engine firings to drive the stages back into the atmosphere for a destructive breakup, making sure any debris falls into an ocean well away from shipping lanes or populated areas.

By taking Falcon 9 upper stages out of orbit after their missions, SpaceX ensures they will never pose a collision risk with other spacecraft or add to the space debris already in low-Earth orbit.

During launch of 20 Starlink internet satellites on July 11, the Falcon 9’s second stage malfunctioned and failed to complete a “burn” needed to reach the proper orbit. Stuck in a lower-than-planned orbit, all 20 satellites fell back into the atmosphere and burned up.

SpaceX briefly suspended flights at the direction of the Federal Aviation Administration, but the problem was quickly identified and fixed, and the company was allowed to resume flights while the investigation continued.

Then, during another Starlink launch on Aug. 28, a Falcon 9 first stage descending to toward landing crashed onto the deck of an off-shore drone ship. SpaceX has not provided any information about what went wrong or what, if any, corrective actions were required, but flights resumed three days later.

SpaceX provided no details about the off-target re-entry of the Crew Dragon’s upper stage other than the post late Saturday on X.

SpaceX

Going into Saturday’s launch, SpaceX was planning to launch 20 OneWeb broadband satellites from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California this week, followed by a Starlink launch from Cape Canaveral. Both flights are now on hold.

More important, a Falcon 9 will be used to launch the European Space Agency’s $390 million Hera asteroid probe from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station around Oct. 7, followed by launch of NASA’s $5.2 billion Europa Clipper Jupiter probe from the Kennedy Space Center on Oct. 10.

Hera is bound for the asteroid Didymos and its moon Dimorphos, a small body that NASA’s DART probe crashed into in 2022. Hera will study the system in detail to determine how the moon’s structure and orbit were changed by the impact. A primary goal is to learn more about how an asteroid threatening Earth some day might be safely diverted.

The Europa Clipper is a “flagship” mission to explore Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa and to determine the habitability of a vast sub-surface ocean. It is the largest planetary probe ever built, requiring a powerful Falcon Heavy rocket, made up of three strapped-together Falcon 9 first stages and a single upper stage, to send it on its way.

Both missions must get off the ground during relatively short “planetary” launch windows defined by the positions of Earth, Mars, Jupiter and the asteroids. Hera’s window opens on Oct. 7 and closes on Oct. 25. The Europa Clipper launch window opens on Oct. 10 and runs through Nov. 6.

Missing a planetary window can result in long, costly delays while while Earth, Jupiter, the asteroids and Mars, needed for gravity assist flybys, return to favorable orbital positions enabling launch.

Armando Piloto, a senior manager with the Launch Services Program at the Kennedy Space Center, said the Falcon Heavy stages used for the Europa Clipper mission will not be recovered. Instead, they will consume all of their propellants to achieve the velocity needed to send the probe on a five-year voyage to Jupiter.

“I’ll point out that during the burn of the second stage, the vehicle with the spacecraft, will be traveling approximately 25,000 miles per hour, which will be the fastest speed for a Falcon second stage ever for Europa Clipper,” he said during a recent briefing.

Given SpaceX’s rapid recoveries after the July and August malfunctions, the upper stage re-entry anomaly Saturday presumably will be resolved in time to get the Europa Clipper and Hera missions off the ground within their launch windows. But that will depend on the results of the latest failure investigation.